A stalwart of the early 2000’s indie revolution and one of its most influential songwriters and trendsetters; Carl Barat’s illustrious career will be looked at fondly by history. As half of the effortlessly enigmatic partnership between himself and fellow libertine Pete Doherty, he conjured up some of the most important moments of Britain’s musical culture over the last two decades, enthralling and inspiring a throng of disenfranchised youths to venture on the path toward Arcadia.

Recruiting the band via social media, the group released a slew of well received in the run up to the album’s release and many believed that the Basingstoke born troubadour was on track for another successful reinvention. Much to the music world’s delight, they hadn’t misplaced their trust.

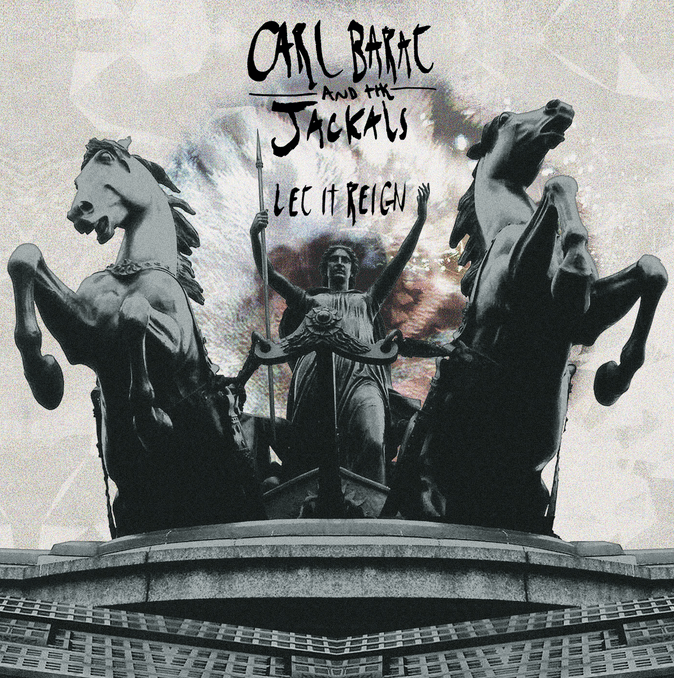

The new outfit’s debut Let It Reign is a solid and well paced album brimming with hypnotic riffs, quip laden lyrics and wry social commentary that manages to provoke thought as opposed to preaching to its audience.

Beginning with squalling, Squire-esque guitar, Glory Days is a swaggering rock ‘n’ roll track that is reminiscent of Barat’s acclaimed Dirty Pretty Things in its relentless nature. Lyrically, it finds him harking back to his younger days in tone a that demonstrates fondness and spite in equal measure.

What follows is one of the first allusions to a bygone era that are both a lyrical and musical theme throughout the record, with the maudlin horns of Victory Gin’s intro giving way to a frantically paced composition. It’s chorus is also notable of another thematic undercurrent running throughout the record; that of Orwellian imagery and ideals. The dystopian work of George Orwell in novels such as 1984, Animal Farm and the non-fiction An Homage To Catalonia has clearly informed many aspects of the album’s conception, with Barat frequently calling for a political and cultural upheaval throughout.

Speaking of which, the relentless barrage of guitar parts and pulse racing percussion of Summer In The Trenches finds him examining the apathy of our modern generation whilst refusing to chastise the aforementioned youth for their approach. musically, it finds itself adopting aspects of proto-punk’s unhinged and aggressive sound whilst utilsing modern production techniques to great effect.

The closest that the album comes in terms of a mobilising call to arms, A Storm Is Coming‘s central guitar work harks back to Gang Of Four at their most potent whilst Carl’s rhetoric focuses upon the proletariat and urges them to rise up. A modern day protest song in the mould of folk musician’s such as Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan, its infectious and fuzzy guitars are in contrast to its poignant message.

Turning his attention to the concept of religion and its oppressive hold upon many, Beginning To See proclaims the benefits of secularisation as opposed to a faith based society. Driven by acoustic guitar and Barat’s wistful vocal, it is one of the poppier moments on the album as it subverts from the rugged and unkempt rock and roll of previous tracks.

Delving back into more strident territory with ‘March Of The Idles’, its lyrics once again focus themselves upon opposition to what its composer perceives to be the inherent conformity and disconnection of Britain’s public. Fueled by a riff that wouldn’t be out of place on a latter day Strokes album, it finds Carl more willing than ever to stray from the romanticised notion of Anglophilia that ran throughout The Libertines, The Dirty Pretty Things and his short-lived solo juncture towards the grittiness of The New York Dolls and The Stooges to name a few.

We Want More is without doubt the album’s low point, featuring cliched and irking gang vocals over a nondescript riff, before the LP regains momentum with War Of The Roses; on which Barat and his new found bandmates place their unique spin upon the colossal sound of recent Queens Of The Stone Age output that made Like Clockwork such an unreserved joy.

The Gears is markedly abrasive compared to the rest of the album; harking back to the sound of Still Little Fingers in their heyday albeit with a distinctly English twang, whilst Let It Rain provides the album with a suitable conclusion, recalling both the reflective and observational themes of the album over a britpop infused backdrop.

Clearly not content to rest on his laurels and muse over past triumphs, Carl Barat and The Jackals have crafted an album which approaches serious matters and personal dilemmas with warmth and genuine passion over a soundtrack of both melodic and ferocious rock; paying homage to the nuances and subtleties of respective genres whilst refusing to be restrained by the preconceived notions that surround their legendary frontman.

The record won’t galvanise the youth in the manner that Barat’s exquisitely composed lyrics suggest but it certainly proves that he can inject new life into a stellar career that has often been overshadowed by the looming presence of The Libertines.