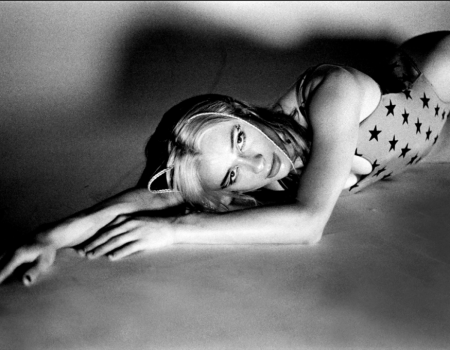

DAVID Bowie’s 25th studio album, Blackstar, released just three days before his untimely passing at the age of 69, serves as a welcome reminder of how much the man, the myth, the enigma, shaped the worlds of music and culture in the last five decades.

It’s an emotional listen and thoroughly fitting epitaph to the genius of the chameleon like character that, a full 47 years after his debut album, David Bowie, refuses to allow itself to be pigeon-holed within a certain genre, an accolade that Bowie has worn as proudly to his person as the patch on his eye ala Ziggy Stardust.

To leave us with this gift, this work of art, is a mark of the man himself. Perhaps ‘man’ doesn’t quite cut it here. Ethereal being. Someone, something who stumbled into all of our own consciousness’s at some point or other and whose spirit will remain, indefinitely.

Bowie’s last hurrah is one that could have fooled even the staunchest fans, taking the artist into experimental territory the likes of which we haven’t seen previously. It seems that, after freeing himself from the shackles of the ‘comeback’ album that was 2013’s poorly received ‘A New Day’, Bowie has kept with the ‘no fucks’ approach and pushed the envelope further. There’s a distinct Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly feel about it, and it comes as no surprise that Bowie said that Blackstar was influenced by the Compton rapper’s sprawling opus.

Recorded mostly in New York’s Magic Story studio under the guise of long term producer Tony Visconti, Blackstar is noir in its purest sense, with free form jazz, synth pop, electronic and drum and bass influences coming together to form a work of such depth and variety the likes of which could only be pinned to a Bowie label.

It’s also most definitely a ‘band’ record, with Bowie’s own soaring, haunting vocals married to the electric sounds of the avant garde jazz quartet the Donny McCaslin Quartet (saxophonist/flutist McCaslin, keyboardist Jason Lindner, bassist Tim Lefebvre, drummer Mark Guiliana) and guitarist Ben Monder.

It’s worth noting from the outset how well they deliver on the album, especially Donny McCaslin on saxophone, as they play with an air of carte blanche freedom and inspiration that provides Blackstar a perfectly Bowie-esque signature, sedative, other-worldly sound, in the same vein as those accompanying Miles Davis or John Coltrane on the likes of ‘Kind of Blue’ and ‘Love Supreme’.

Running rich through the album are themes of death and despair, with references to the Bible, the afterlife and psychosexuality, with Bowie himself in the role of noir narrator. Themes of doom, however, aren’t new to Bowie, as we have witnessed in the likes of ‘Space Oddity’. It’s only here, however, that, since his death, his lyrics retain that extra resonance.

Opener ‘Blackstar’, at nearly 10 minutes long, leads on a true Labyrinth like sojourn, as Bowie broods of solitary candles in Norwegian villages and executions. Initial staccato drums and moody electronica, reminiscent of Boards of Canada, juxtapose with a jazzy, slow pop sound marked by Bowie’s morbid vocal.

‘Tis a Pity She Was A Whore’ motors along against Mark Guiliana’s pounding drums and McCaslin’s screaming sax, as the equally colloquial/archaic tale of mysogony sees Bowie go all English renaissance, to great effect.

With ‘Lazarus’ a slight XX tinge leads us into a lingering post-punk sound, with Bowie’s “Look up here, I’m in Heaven” lyric having an altogether added sense of emotion.

Murder ballad ‘Sue (Or in a Season of Crime)’, punctured by irregular beats and sonic synths takes on a space-like jungle feel, while Bowie’s yelp of “Where the fuck did Monday go?” on ‘Girl Loves Me’, against strings and cinematic touches bring the man into mild rap territory.

‘Dollar Days’ is the closet to conservative and conventional we get on the album, as Bowie sings with a sense of bitterness through “If I’ll never see the English evergreens I’m running too/It’s nothing to me/It’s nothing to see”, with touches of Nadsat, the lingo/dialect of Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange, thrown in for good measure.

Lastly we have ‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’, a poignant farewell that reads as a defence of his penchant for, up until his last days, remaining in relative obscurity, away from the music industry spotlight.

Blackstar is an audacious, intriguing album that, although not quite a return to his halcyon Berlin inspired days, is undoubtedly his best work since 1983’s ‘Let’s Dance’. Once that requires further listens to fully appreciate its depth and quality, without being in any way inaccessible.

Even as his time on Planet Earth drew to a close, the Spaceman showed us that it’s never too late to be original.